Mogg Hegon & Henry Jocelyn

Come to an Agreement

By Pat Higgins

In the summer of 1675 a fierce and bitter war erupted in Massachusetts between the English settlers and the Wampanoags under Metacomet or King Philip. It was not long before hostilities spread to Maine. The touch point was the infamous story of the death of the sagamore Squando's infant son. The baby was drowned when his mother's canoe was upset in the Saco River by English sailors testing the theory that Indians swam naturally, 'like animals', from birth. Soon the Maine frontier was in flames.

Our little story takes starts on October 12, 1676 at Black Point (Prouts Neck in Scarborough). Interestingly, less than 200 hundred years before on October 12th, Columbus "discovered" America. In 1676, Black Point was overrun by Indians who were supremely tired of the white man, and it was abandoned by the English for the first (but not the last) time.

For another Maine Story about King Philip's War, read Ann Mitton Brackett: Needlewoman to the Rescue.

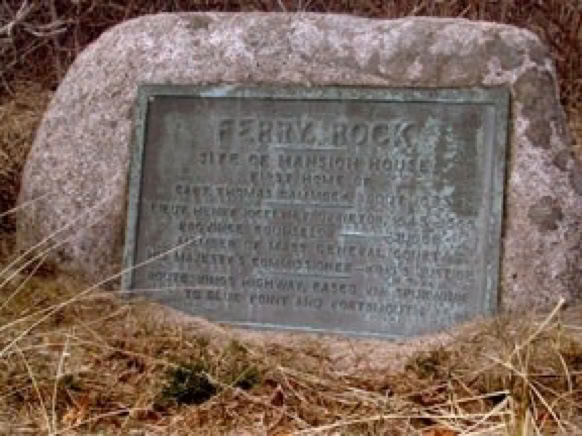

Black Point and the Principal Players: Black Point was settled in 1631 by Thomas Cammock who arrived from England via Piscataqua with a patent for 1500 acres. Within a very short time he set up his own little feudal kingdom with 50 cottages at Ferry Point for workers engaged in fishing, farming, trading and operating fish flakes and a saltworks. The location is marked by a plaque at the corner of the golf course where the Scarborough River enters the ocean. In 1643 Cammock died leaving his property divided equally between his wife and his business partner Henry Jocelyn. After a decent period of morning, Jocelyn married the Widow Cammock and assumed complete control of the Patent.

Jocelyn was a prominent leader, judge and even governor on the Maine frontier over the next thirty years. He was also the brother of John Jocelyn author of "The Voyages of John Jocelyn Gent." an important source of information, fact and fiction, on 17th century Maine. By the 1670's Jocelyn was aging and in financial difficulties brought on by a lifetime of civil service to the neglect of his own business interests. He sold out to a prosperous Boston merchant, Joshua Scottow, but stayed on as a sort of manager and supervised the building of a garrison house on the west side of the Neck.

Throughout 1675 and 1676 the neighboring Indians with reinforcements from the Kennebec tribes raided farms and outposts, stole cattle, burned buildings and killed isolated settlers. Scottow brought in troops from Boston and supplied powder and sanctuary to his neighbors. These grateful people charged him with refusing to allow the troops to defend them and instead using the same soldiers to cut his wood, move his barn, pave his yard, etc. Scottow spent the fall of 1676 in Boston defending himself from his neighbors. He left Jocelyn, Walter Gendal, and Sergt. Tippen in charge of the garrison while he was away.

The primary Indian sachem in our little story was Mogg (Mugg, Mogg Hegon) who was well known to the white settlers. Mogg's principal hunting grounds lay between the Saco and the Kennebunk Rivers. He and his father, the sachem Walter Hegon, both used the name Hegon which means "arrow point". This refers to the point of land that juts into the ocean at the Biddeford Pool boundary of their hunting grounds. The mouth of the Saco was often visited by the English from the earliest times. Certainly Mogg grew up amongst the English and spoke their language. In 1664 he deeded all of his lands as far inland as Salmon Falls to Major William Phillips. During the summer of 1676 Mogg acted as an intermediary between the colonists and Squando; certainly he was not considered at that time to be an "enemy Indian". Perhaps his mind was changed during all the time spent in the tribal councils. Acts of treachery by both sides ended any likelihood of peace.

The Attack on the Garrison:At any rate, on October 12th one hundred Indians under the leadership of Mogg appeared before Scottow's garrison. Knowing the house was too strong, they did not attack. Being elderly and not wanting to fight, Jocelyn agreed to come out and talk peace. Mogg and Jocelyn knew each other well, or certainly Jocelyn would not have done so. According to William Hubbard's Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians of New England, Mogg "showed more courtesy to the English than according to former outrages could be expected". The sachem said that if the garrison surrendered, the occupants would be allowed to leave peacefully.

Although this would not prove to be so in later Indian wars, Jocelyn could expect to rely on Mogg's word this time because of the sachem's long, friendly association with the settlers. Jocelyn returned to talk it over with his people only to find the garrison empty except for his family. The others had used the opportunity to escape by boat! Jocelyn did the only thing he could do- surrender. This was not the first time in his long career as a public servant in tumultuous early Maine that his neighbors ran out on him. Jocelyn and his family were well treated and set free in the spring. Jocelyn never returned to Black Point. One can hardly blame him! Instead he went to Plymouth and then to Pemaquid. Jocelyn held a minor government position there until his death in 1683.

Later that same day, October 12th, Mogg's forces captured a 30 ton vessel at Spurwink. Walter Gendal was loading his household possessions with the help of eleven others including the ship's crew and members of the Black Point garrison. They were taken by surprise and did not know the garrison had already fallen. Thus Mogg captured what was reputably the strongest garrison in the east, a ship and more than a dozen prisoners in a single day! Gendal shrewdly dubbed Mogg "generall".

The Indians neither destroyed the Black Point garrison on that October day nor remained in the vicinity long. Perhaps, in light of his recent successes, Mogg believed the English would soon be driven from the country. Unfortunately difficulties between the colonists and the Indians in Maine had hardly begun.

View from the corner of the present day golf course with Ferry Rock in the foreground and Pine (Blue) Point on the opposite shore. The sweep of Saco Bay and Old Orchard Beach are just visible on the horizon.

The lay of the land on both sides of the Nonesuch have been remarkably changed in recent years by a breakwater built at Pine Point during the 1960's to protect the harbor.

The inscription reads:

Ferry Rock

Site of Mansion House

First Home of

Capt. Thomas Cammock about 1633

Lieut. Henry Jocelyn, Proprietor 1643-1666

Province Counselor - Judge

Member of the Mass. General Court

His Majesty's Commissioner - King's Justice

Route: King's Highway, Casco via Spurwink

to Blue Point and Portsmouth

The Aftermath:The war party divided, and some sailed to Penobscot in the ship with some of the captives. Mogg took his captives to Wells where he used Gendal as his emissary to induce the inhabitants to surrender. Gendal pleaded with them to no avail. It was a no win situation for Gendal. If the garrison surrendered, General Mogg would have more prisoners; if it did not or Gendal did not return, the Spurwink hostages were endangered. However, it did not appear that Mogg would win another easy victory. Instead of attacking the garrison, the war party continued on towards Piscataqua where Gendal arranged a safe passage to Boston for Mogg to exchange prisoners and talk peace. In Boston, Mogg seems to have had a change of heart, or perhaps the tables were turned, and he became the hostage emissary. Either way, he was soon on his way to Penobscot to treat with Modockawando and redeem English captives.

Scottow was probably greatly surprised by the surrender of his garrison as he considered it absolutely secure. By October 25, 1676, around the time Mogg was in Boston, Scottow received permission from the General Court to "send forth a smalle vessell or two with company for the discovery of the state of the fort at Black Point and transport of what may be there recoverable either of his or any other Inhabitant" and if possible reinhabit the area. The Indians were gone; the garrison was remanned by a company of soldiers under Bartholomew Tippen, one of the people who had abandoned Jocelyn to the Indians only a short time before. The settlers gradually returned. Black Point was not troubled again until spring.

In the spring Mogg returned to southern Maine from Penobscot with his allegiance again with his own people. On May 13, 1677, a great band of Indians, again led by Mogg, attacked the Black Point garrison. This time they bit off more than they could chew. This time, Tippen was a real fighter. It was a life or death struggle for those in the garrison. Tippen successfully defended the garrison for three days, loosing only three men. On the third day, Tippen himself shot and killed Mogg. The warriors were so disheartened by the loss of "the most cunning Indian of his age" that they withdrew but not for long. This was only the beginning of Maine's Indian wars.

Some Modern Connections:An interesting little finale to Mogg's war party happened two hundred years later in the 1880's. While planting trees behind the Willows Hotel on the Prouts Neck, Alvin Plummer uncovered a human skull. Further investigation turned up fifteen male skeletons, perfectly preserved, and arranged in sitting positions around a larger central figure. The central skeleton was adorned with wampum and a copper breast plate. After careful analysis by members of the Maine Historical Society, it was determined that interment was made in the mid to late seventeenth century. The only logical explanation is that the sight was the burial place of Mogg and his tribesmen who lost their lives in the 1677 attack on Jocelyn's garrison. Before retiring, the surviving tribe members must have buried their bodies in a sort of council of the dead.

Plummer tenaciously refused to part with his treasures. For years, he had his own private Indian museum in a shed on Prouts Neck. Occasionally, he shared it with a few lucky tourists. After Plummer's death, a few self-righteous people buried the remains in some unknown spot.

In 1836, Mogg Hegon was immortalized by John Greenleaf Whittier in the epic poem Mogg Megone. Whittier, a Quaker from Haverhill, MA, is perhaps better known for his poems on abolitionism and on the natural landscape and rural life of New England. As a poet, he is not highly rated today; his work is idyllic and sometimes maudlin. Whittier himself confessed that Mogg Megone is not one of his better works. In a letter to The Century Magazine, Whittier explained his inacuracies by saying: "It was written in my boyish days when I knew little of colonial history or anything else". A quick once over will tell the reader that the poem does not much follow the real life story at all.

The name Henry Jocelyn resurfaced again during World War II. Liberty ships were named for eminent Americans from all walks of life who had made notable contributions to the history and culture of the United States. Bath Iron Works and Todd Shipbuilding built many ships at their South Portland Yards. Many were named for famous Mainers including Joshua Chamberlain, Thomas Brackett Reed, Hannibal Hamlin and William Pepperel. The Henry Jocelyn was a Liberty Class 441 freighter built for the U.S. Maritime Commission and launched in August of 1943. Perhaps the ship was reward for faithful service as well as recompense for the poor treatment he received at the hands of his fellow Mainers.

Sources: Cornell University. Making of America. "Whittier, John Greenleaf." • Hight, Horatio. "Mogg Heigon- His life, his death, and its sequel". Maine Historical Society. Vol.5. May 31, 1889. • Libbey, Dorothy Shaw. Scarborough Becomes a Town. Freeport, ME: Bond Wheelwright,1955. • Moulton, Augustus. Old Prout's Neck. Portland, ME: Marks Printing House, 1924. • Toppan, Andrew.Production Record of Todd-Bath Iron Shipbuilding,1940-1942; South Portland Shipbuilding,1941-1943; New England Shipbuilding,1943-1945.http://www.hazegray.org/shipbuilding/.

c2000 Pat Higgins