Popham Colony

A Slice of Time

By Pat Higgins

In 1607, the same year in which Jamestown was colonized in Virginia, the Plymouth Company made their second attempt to establish an English colony in New England. Not many people today realize that there were actually two simultaneous colonizing attempts, Virginia and New England, because the northern colony at the mouth of the Kennebec River didn't last but a year. Jamestown takes all the honors as the first permanent English colony in North America; Jamestown and Plymouth are near mythic in American history, but Popham Colony is hardly even a footnote.It could have all happened so differently.

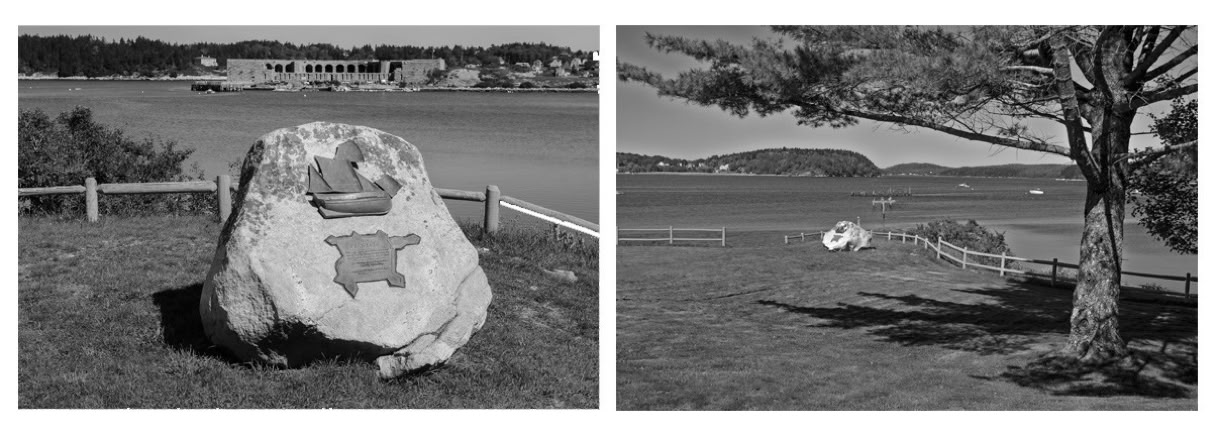

Panorama of the Popham Colony site. The fort was located in the field at center. Dave Higgins photo

The English colonization of North America was not a quick decision. Powerful Spain made it abundantly clear that any lands south of Florida were off limits. Thus, France and England both conducted explorations of the northern coast in search of the Northwest Passage to the Orient. There had to be one, didn't there? Nearly a hundred years of escalating exploration starting with John Cabot, who sailed the American coast with a patent from the English king Henry VII in 1497, exhausted this possibility. Gradually, as explorers and fishermen brought back tales of great natural resources in fish, lumber, fur, and much more, the focus began to change.

The first decade of the 17th century brought new interest and participants to exploration and colonization efforts. A series of voyages (Gosnold, Pring and Waymouth) and political maneuvers (the Virginia Company charter) built one on the next and led directly to Popham Colony.Based on the information discovered by exploration, the work of Sir John Popham and Ferdinand Gorges paved the way forfinancial backing and the colonization effort.Waymouth's voyage in 1605 was perhaps the most important as he was charged with finding a Maine location for the establishment of a colony. In addition to the information provided by his exploration as recorded by James Rosier, Waymouth brought back five kidnapped Pemaquid natives:Dehanada, a Sagamo or commander, and Amoret,Skidwarresand Maneddo, all listed as Gentlemen, and finally Sassacomoit, a servant. (Sabino, 59) The names vary widely in spelling over the next few years.

Waymouth turned the captives over to Gorges who sent two on to Popham. Gorges was immediately charmed by his Indians and pumped them for information. He considered them sent by God to help in his colonization efforts; they quickly became his best source of information to date. Much later, he wrote in his A Briefe Narration of the Originall Undertakings of the Advancement of Plantations into the parts of America:

"The longer I conversed with them, the better hope they gave me of those parts where they did inhabit, as proper for our uses; especially when I found what goodly rivers, stately islands and safe harbors those parts abounded with, being the special marks I levelled at, as the only want our nation met with in all their navigations along that coast. And having kept them full three years, I made them able to set me down what great rivers ran up into the land, what men of note were seated on them, what power they were of, how allied, what enemies they had and the like." (Baxter, Sir Ferdinando Gorges and the Province of Maine, 9)

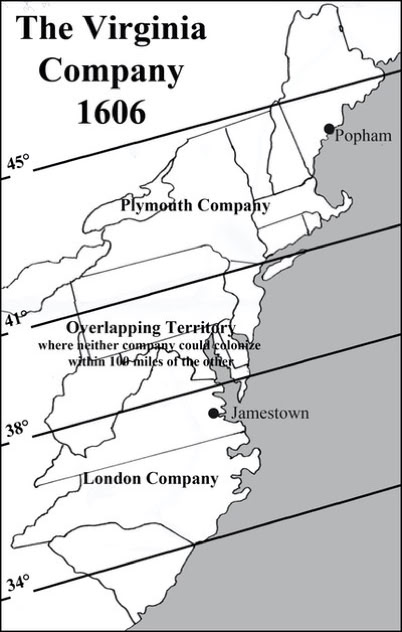

Map - Pat Higgins

By the time of Waymouth’s return a completely new game plan for colonization was afoot. In April of 1606 King James I signed a charter for the Virginia Company with the express purpose of establishing colonies in North America. The Virginia Company was actually composed of two joint venture stock companies and modeled after an early version of the East India Company, a trading monopoly of London merchants chartered by Elizabeth in 1600. The two Virginia companies were nearly identical except for their theaters of operation. The LondonCompany, so named because its primary investors were London merchants under the leadership of the king's Secretary of State Sir Robert Cecil, were granted rights of settlement and trade between the 34th and 41st parallels. The Plymouth Company, composed largely of gentlemen and merchant investors from the West Country and centered around Plymouth with Chief Justice Popham at their head, were granted lands between the 38th and 45th parallels. It was further stipulated that each company's territory extended 100 miles inland from the coast and that no colony could be established within 100 miles of the other company's colony, thus the overlap. This neutral zone would eventually be added to the area of the first company to establish and maintain a stable colony. The primary objective was, of course, to make money for the investors and the crown who was to receive 20% of the net profits from precious metals, however, the king retained absolute control of the colonies. It seemed a good deal and, in light of all the exploration propaganda, a sure fire moneymaker.

A “family-related pool of candidates” – Jeffrey Brain

Both branches of the Virginia Company, London and Plymouth, began to plan for colonization and to put together the necessary people, ships and materials in order to set sail as quickly as possible. Land and profits hung in the balance.

The people involved with the Plymouth Company included many familiar names from previous voyages and also many men who would be involved with the settlement of Maine and North America into the future. Gorges and Popham were prime movers in the Plymouth Company but quite different men. Sir John Popham, Lord Chief Justice of England from 1592 until his death, was the primary investor. He is a well known figure in English history whose life is intertwined with all the famous names of the period. Popham’s dissolute youth in the West Country is legendary; he was prone to keeping bad company, drinking and gambling to excess and to frequent activities as a highwayman. Marriage and the death of his father forced him to come around and take up the other side of the law. Known as the hanging judge, he was a large, severe and ugly man who scared the living daylights out of those who appeared before him in the dock. Many famous people were tried before the Judge including Mary Queen of Scots, the Earl of Essex, Guy Fawkes of the Gunpowder Plot and even Walter Raleigh. Popham was intelligent, dependable and well versed in English law but not known to be beyond the occasional bribe.

On the other hand, Gorges was a second son who followed military training with service in France as a young captain. He fought at Sluys in 1587, was captured and imprisoned during the invasion attempt of the Spanish Armada in 1588, and was wounded at the siege of Paris in 1589. Like many military men of his time he served both on land and at sea. He was knighted in 1591, and by 1595, having made his mark as a reliable and efficient officer, he was sent to Plymouth harbor to build and command fortifications for Devonshire. Many of his military services brought him into contact with Walter Raleigh, the earls of Essex and Southampton and the Popham family. His relations with these men gave him an interest in colonization but exposure to Waymouth’s captives incited a great passion that directed the course of his life right up to the time of his death. Interestingly, neither Sir John nor Sir Ferdinando ever set foot in North America.

Much of the colony’s foundational work fell to Gorges who was particularly qualified for the job at hand. His job was to facilitate; Popham was to be the moneyman. Others were soon involved. Interestingly enough, as Jeffrey Brain points out in the preface to his Fort St. George, it was a nepotistic bunch. Walter Raleigh and Humphrey Gilbert’s mother was Catherine Champernowne; both Gorges and Popham were related by marriage to the Champernonwnes. A loosely related list of other colonists soon come together: Popham’s son Francis, his nephew George Popham and grandnephew Edward and his grandson Captain James Hanham; Sir Humphrey’s son Raleigh Gilbert; captains James and Robert Davies who were likely relatives of the navigator/explorer John Davies, another Gilbert relation; Chaplain Richard Seymore was both a Gilbert and a Gorges cousin and related to the Pophams; Gome Carew, the company metallurgist, was related by marriage to Sir Walter whose brother was named Carew; and even John Hunt the draftsman of the famous Popham map might have been a Popham relation by marriage. In some ways it seems a limited gene pool, but according to Professor Brain, “it is clear that an effort was made to select wisely from the available family-related pool of candidates.” (Brain, 5)

The Plymouth Company was the first out of the starting gate. The first ship, the Richard, set sail in August 1606, was captained by Henry Challons and carried two Waymouth captives, Maneddo and Assacomiot, to act as interpreters. The second ship was in the command of Popham’s grandson Thomas Hanham and Martin Pring who previously sailed the coast of Maine at least twice before. Traveling with them was Dehanada, the captured sachem. In October, Hanham and Pring sailed directly across the Atlantic by the northern route but could not find Challons in Maine with good reason. Against specific orders, Challons took the southern route and was captured by the Spaniards off Florida in November. The two ships were supposed to find a sight previously selected by Waymouth (probably on the St George River) and set up the beginnings of the colony for the main expedition that would follow in the coming year. Without Challons and having no idea what became of him, Hanham and Pring explored a wider area than Waymouth, perhaps at Dehanada’s direction. Ultimately they preferred the Sagadahoc over Waymouth’s “most excellent river”, but chose to sail home with all hands save one leaving the actual colonizing to the full expedition. Dehanada was left behind at Pemaquid. In late December 1606, the Jamestown colonists sailed from England and the opportunity to be the first colony was lost to the Plymouth Company.

“An inward disease” – Henry O. Thayer

Popham was not only the judge’s nephew but he was also an experienced soldier, privateer and perhaps mariner. George Popham is one of four named in the original Plymouth Company charter in 1606. As president of the colony he also may have been a little long of the tooth as historian Henry Thayer implies, but certainly not as old as in his seventies. Most modern historians peg him as a man in his fifties. Gorges characterized him as “an honest man, but old, and of unwieldy body, and timorously fearful to offend or contest with those that will or do oppose him, but otherwise a discreet, careful man”. (Thayer, 28) Others describe him as infirm; age and experience may not have been the best combination for his position.

The main expedition left Plymouth with 120 colonists and an unknown number of sailors on May 31, 1607 on two ships, the Gift of God commanded by George Popham and the Mary and John under Raleigh Gilbert. These two men were to be the colony’s leaders, and two more different men would be difficult to find. It was not a partnership that was likely to work well, if at all. As historian Thayer described it, in the end it was “an inward disease, more than outward ills, not indeed wanting, weakened it, so that a slight stroke in the end broke the resolution of the company”. (Thayer,34)) Planning and supply were not wanting, but leadership and direction were.

Raleigh Gilbert was admiral and second in command of Popham Colony. He was also one of the original four designated by the charter and was connected to the history of exploration and colonization through his father Sir Humphrey. In all other ways he seems the antithesis of George Popham. Gilbert was young, in his mid-twenties, and vigorous, quick and full of energy. However he also lacked the patience, discretion and experience necessary for leadership. Gorges described him as “desirous of supremacy, and rule, a loose life, prompte to sensuality, little zeale in Religion, humerouse, head-stronge, and of small judgement and experience, other ways valiant inough.” (Baxter,80) Youth and pigheadedness would also not work well for the colony’s leadership.

In addition to the two leaders and other gentlemen of quality very few members of the colony are known by name. These would be the proposed settlers and the common seamen. The settlers consisted of soldiers, traders, farmers and craftsmen particularly carpenters. Chief Justice Popham looked at colonization as a possible place for the overflow of English population and also as a possible place to banish vagrants, criminals and other undesirables. It is not known how many of Popham’s colonists previously called England’s gaols home as has been implied by many historians.

Today what we know about what actually happened at Popham Colony comes from two basic sources. The first is Relation of a Voyage to Sagadahoc by a supposed unknown member of the colonists. Unlike the recent explorations leading up to the colonizing effort there appears to have been no known official recorder of events and information. If there was such a person or document they are lost to us at the present time. The Relation starts with the expedition setting sail from the Lizard in England and continues to October 6, 1607 when it comes to an abrupt end. Only about a quarter of the document deals with the time period in which the party landed at Sabino Point and began their construction efforts. Why October 6th? Because within a day or two of that last entry, the Mary and John set sail and returned to England. The author of the Relation was Captain Robert Davies of the Mary and John and was clearly identified in the second contemporary source: The historie of travaile into Virginia by William Strachey. In reading the second account it becomes evident that Strachey had a copy of Davies’ Relation as the structure and much of the wording is similar and often identical. Strachey knew Davies from their time at Jamestown in the years after Popham and so probably had access to the document as well as conversations with Davies himself. That said, the Strachey account does not include anything on the time between early October and Davies return the following spring. There are few other documents about Popham Colony activities beyond Gorges’ manuscripts and some letters, notably one from George Popham in December 1607. In his continuation of Hakluyt’s work of collecting colonization documents, Samuel Purchas makes reference to having at hand documents and journals from many particpants in his Purchas His Pilgrimage of 1613 but he does not impart hardly any of this information to the reader. The items that he refers to appear to have disappeared.

“They all presently Isued forth towards us wth thear bows & arrows”

- The Relation of a Voyage unto New England

The two ships, separated at sea, reunited off Weymouth’s St George Islands on August 7th. This had little to do with either Popham or Gilbert’s skills as seaman but was rather based entirely on the skills of the two real captains, Robert Davies of the Mary and John and John Elliott captain of the Gift. The first order of business included another very important passenger, Skiddwarres, the last of Waymouth's Indians. The colonists expected to reconnect with Dehanada and then move on to Sagadahoc. This did not progress as well as they expected or hoped. Skiddwarres reluctantly guided Gilbert and thirteen men in the ship’s boat into New Harbor. They walked across the peninsular to the village on Pemaquid Harbor where they were met by about a hundred native men, women and children. At first sight of the Englishmen the natives made a “howlinge or Cry … they all presently Isued forth towards us wth thear bows & arrows” (Sabino, 430) Things could have gone very badly for these obviously untrustworthy and unwelcome visitors if Skiddwarres and Dehanada had not caught sight of each other. From a distance it seems evident to us now that the Native Americans were becoming increasingly distrustful.

Two days later both colony leaders sailed their ships’ boats into Pemaquid Harbor opposite the native village causing more upset. Skiddwares was again brought forth to speak to the massing tribe. After a parley the natives went off into the woods and did not return. Skiddewarres also would not return to the ships with the English “promyssinge to retorn unto us the next Daye followinge but he heald not his promysse.” (Sabino, 431) That the natives were distancing themselves did not bode well for the colony’s purpose of trade or for good neighborly relations.

“Labored hard in the trenches” - The Relation of a Voyage unto New England

On August 16, 1607, theGift of God and the Mary and Johnentered the mouth of the Kennebec River in what is now Phippsburg. This was the area that Pring and Hanham described as the ideal colony location the year before. Popham and Gilbert then took to their boats again and sailed up river about 14 leagues, as recorded, to explore. This would be about as far as Augusta, but that seems an unlikely distance for this trip. They liked what they saw. On the 19th the colonists went ashore at the mouth of the river on Sabino Point, their chosen site. They listened to a sermon by Richard Seymore, the first known religious service held by Englishmen in North America, and a reading of the charter, and then began to plan the settlement. The fort would be called Fort St George like just about everything else the English named during this decade of exploration. At the time the lower Kennebec was known as the Sagadahoc, and the little colony is also frequently referred to as Sagadahoc Colony or as Popham Colony after Sir John Popham their chief patron.

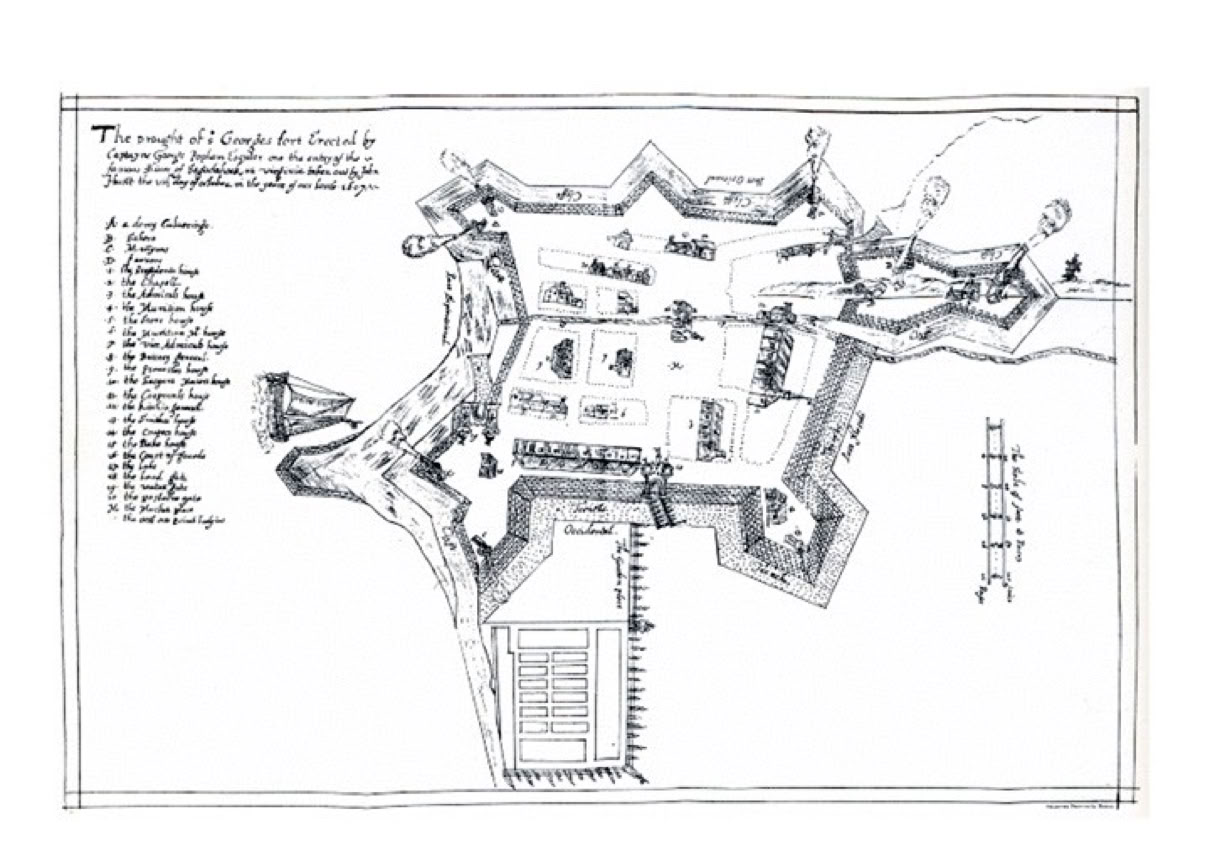

Hunt's map of Fort St. Georgefrom Thayer

The following day all hands made an ambitious start at building an earthwork fort, a church, a storehouse and fifty houses. The Relation tells us that Popham started things off with the first shovel full and “after hem all the rest followed & Labored hard in the trenches”. (Thayer,67) Colonist John Hunt left a remarkable diagram of Fort St. George showing the placement of these buildings, stonework, gates, parapets, cannons, and flags. Although modern archaeology has proved this map to be accurate to a point, the map was made only seven weeks after the colonists landed and so can hardly be considered a picture of the completed facility but rather the colony as planned and begun. It is the only map or diagram of an initial English colonization effort available to modern historians. The archaeological work of Professor Jeffrey Brain confirms the location and the construction of the storehouse and Admiral Gilbert’s House in the locations of Hunt’s map, but the storehouse is one bay short of the dimensions Hunt stipulated. These two buildings plus the church are also mentioned in contemporary sources further proving their actual existence. Beyond that it is much more difficult to prove which buildings were real and which were only planned. It seems likely that, if Gilbert had a house, then President Popham would also warrant one. There may also have been some specialty buildings as well such as a forge.

Another building project was the colony’s most well known claim to fame: the Virginia of Sagadahoc, a pinnace of 30 tuns. Hunt includes the Virginia with full sails anchored near the jetty. The rigging, the sails and iron were brought from England along with a Master Digby, shipwright. Wood for the ship was harvested and milled locally. Of course, the boat and the jetty were not finished at the time the map was made. The building of the Virginia itself was quite an undertaking. In all likelihood, as Professor Brain postulates, the Virginia was actually constructed between two rock outcroppings in the area of the proposed jetty. These could be walled off to create a dry dock for construction and removed later to float the Virginia on a high tide. Brain says that perhaps Hunt did not draw a jetty at all but a cofferdam for ship construction. Atkins Bay is very shallow; ships would have a found it impossible to unload at a jetty. Cargoes were probably off loaded from ships anchored in the channel into boats and rowed to the fort. (Brain, 164)

Looking up at the Fort St. George site from the rocky out crop on the shore that may have been used to form a coffer dam where the Virginia was constructed. Dave Higgins photo

“It was a bold and cunning exploit for this agile savage to spike

the Englishmen’s guns.” Henry Thayer

A gentleman such as Gilbert must have tired quickly of the tremendous amount of labor. By the end of August he was anxious to go off exploring and made a trip to the westward exploring Casco Bay. This was the first of a number of exploratory trips made by Gilbert during the fall of 1607. In the interest of discovering their neighborhood and the potential for trade such trips were not unimportant and added to the general fund of knowledge.

A visit by Dehanada and Skiddewarres on September 5th prompted Gilbert to make plans with them to visit the Bashabe or high chief at Penobscot. Due to unfavorable winds Gilbert and his party did not arrive at Pemaquid on the appointed day. When they finally reached the village, it was completely empty. Sailing onward to the eastward hoping to catch up, the party became lost in Penobscot Bay and was unable to find the Penobscot River. They turned back.

A week more of hard work and Gilbert was off again. This time he headed up the Kennebec for the headwaters. This is perhaps Raleigh’s most interesting and telling expedition. Fortunately Robert Davies was on board to give us an account of what happened. Unfortunately the manuscript ends abruptly three days into the trip description with the ragged appearance of lost pages. We are indebted to Strachey, who might have had access to the missing pages as well as to Davies for the details.

On September 23rd, Gilbert started upriver in his shallop with nineteen men. They sailed for three days and on the third day they came up with a low, flat island with ‘downfalls’ on either side. Some historians have described this island as Swan’s Island which is not very far up the river for a two to three day trip even allowing for the Kennebec’s strong currents and tides. Thayer and Nash claim that there is record of just such an island at Augusta which must be the place described. This island was called Cushnoc Island and was covered and altered by a dam in the 19th century. In the account of this trip Davies gives the only description of the abundance and goodness of the land that comes close to rivaling the recorders of previous explorations of the Maine coast. In addition to “mervellous deepe red” grapes, he says, “very good Hoppes & also Chebolls (onions) & garleck and for the goodnesse of the Land ytt doth so far abound that I Cannott almost expresse the Sam.” (Thayer,75)

The following day, September 26th, they were approached by Sabenoa, the self-proclaimed Lord of the Sagadahoc, in what became a distrustful and unfortunate affair. Presumably we can make the following assumptions about the native names of certain locations that we use today. Sabino Point can easily be regarded as a mutation of the name Sabenoa, and the point was noted as the seasonal home of some of the Kennebec Indians by Champlain in his visit to the area only a year or so before. The Sasanoa River that empties into the Kennebec across from Bath Iron Works and connects to the Sheepscot River across the northern edges of Arrowsic and Georgetown islands might also be considered a Sabenoa variation. We can also make some assumptions of the warlike behavior of Sabenoa based on a conversation Gilbert and other colonists had with Dehaneda and Skidewarres that same month about a battle fought between the Pemaquids, including themselves, and Sabenoa’s tribe in which Sabenoa’s son was killed.

Hostages were exchanged before a parley and trade could come about. Gilbert sent one of his men to the native canoes; Sabenoa came forward to the Englishmen. Quickly, the canoes paddled upriver with the hostage, but Gilbert’s shallop was not able to give chase for any distance as the river became shallow and then was blocked by another downfall. Sabenoa indicated that the hostage would be found at the native village a short walk away; he, Gilbert and nine Englishmen set out on foot. Sabenoa was able to regain control of his men at the village, and circumstances became friendlier. After examining some of the English wares the desire to trade seemed to take precedence. It was agreed that the natives would bring skins down to the shallop, and trade would commence.

Within a short period of time, sixteen natives arrived at the shallop in three canoes with only some tobacco and a few small skins to trade. Something was obviously afoot. Gilbert carefully moved his men into the shallop so as to escape but was anticipated by Sabenoa’s warriors. One native boarded the shallop as if to light his tobacco pipe and instead pitched the firebrand used to touch off the gunpowder in the matchlock guns overboard. As Thayer describes the situation:

Guns at the time were ponderous affairs and fired by a match or fuse, which must in some way be kept burning. These Indians had already been so far conversant with Europeans, as to have learned the nature of firearms and the manner of their use. It was a bold and cunning exploit for this agile savage to spike the Englishmen’s guns, as we might say, by throwing overboard the firebrand. (Thayer,79)

This was serious. Gilbert immediately ordered one of his men to step back ashore and grab a brand from their campfire. The man grappled with some of the natives while others grabbed the shallop’s ropes. Once obtaining fire, Gilbert’s men presented their pieces, and the Indians nocked their arrows. After a few harrowing minutes the shallop was able to draw off across the river. Sabenoa sent an emissary to make an apology that Gilbert quickly accepted. They parted as “friends”. Gilbert’s shallop returned to the fort instead of proceeding to the headwaters. Trade with the Kennebecs did not look all that prospective now, and trade with the Pemaquids was cool at best.

"Thunder, lightning, raine, frost, snow all in abundance, the last continuing"

– Samuel Purchase

Within a few days of the Gilbert party’s return from upriver, the Mary and John with its captain Robert Davies left for England bearing news of a colony well established and Hunt’s map to prove it. Very little in the line of a written record continues the colony’s story through the winter and the return of the ships in the spring. Strachey writes with supposition only about the finishing of the fort and the Virginia.

The Gift remained at Fort St. George until December 16th and then it too sailed for England. It took with it dispatches and a letter in Latin from George Popham to King James. The letter extolls the virtues of the natives, the colony and Maine. He claimed there was cinnamon, mace and nutmeg as well as other fine resources in Maine and also reported that the Indians claimed there was a great sea only seven days travel to the west. It could only be the great Southern Ocean as the Pacific was called then. What could Popham have been thinking?

The truth of the matter was the colony was in trouble. Supplies were dangerously low. Before the Gift sailed a general meeting was held where it was decided to return half the colonists to England in order to stretch supplies. Approximately fifty returned, but there is no surviving list, if there ever was one, to say who stayed and who sailed. Professor Brain theorizes that Popham’s power to lead was waning and Gilbert was taking over. Gilbert’s house seemed to be the seat of the local government and was the location of this and probably other of the colonists’ meetings.

The weather quickly became a major problem. The winter was particularly severe beyond any expectations that the Englishmen might have had; after all Maine and the south of France are both on the 45th degree of north latitude. The settlers anticipated a climate that was at least similar to that of England. Recent explorations occurred only in the summer so there was little to show them otherwise. What they could not understand scientifically was that Maine experiences a continental climate and is less influenced by proximity to the ocean than expected. In other words, the prevailing climactic influence is from the west in the form of cold dry air from Canada. Another part of the explanation is that,between the thirteenth and nineteenth centuries, the northern hemisphere suffered what climatologists now call the "Little Ice Age". The winter of 1607-1608 was not only hard in Maine but also across Europe and England.

It is fitting that one of Popham colony’s many firsts was a weather report. True to that old Mark Twain adage "if you don't like the weather, wait a minute", the report recorded the following in a seven hour period on January 18, 1607: "thunder, lightning, raine, frost, snow all in abundance, the last continuing". (Thayer,88) This was the English colonists' first winter in Maine; they did not know that weather in Maine is always unpredictable at best.

“They repelled the savages disgracefully.” – Father Biard

Then on February 5th George Popham died, and Gilbert achieved sole command of the remains of the little colony. We really have little idea of how this worked out because of the lack of any real continuous record. However there are some stories of questionable validity and a few more believable snippets here and there.

Trade with the natives was limited, and relations continued to be strained. At some point trade commenced at the fort, but by late winter, things were out of hand. Father Pierre Biard, a Jesuit missionary, who visited the Kennebec in 1611, heard many stories of the Popham Colony from the Kennebec tribes. Most were unflattering; some were exaggerated or entirely untrue such as the ambush and slaughter of eleven colonists. Others ring true. After indicating that Popham behaved honorably and kindly towards the Indians, Biard wrote, “the English under another commander changed their conduct; - they repelled the savages disgracefully; they beat them, they abused them, they set their dogs upon them with little restraint.” (Thayer,127)

Historian William Williamson reports a couple of “traditional” stories involving natives at the fort to trade being grossly mistreated. In one case, a group of Indians and the colonists had a falling out. The colonists fled the fort. Chaos reigned for a bit; a cask of gunpowder was broken open and an explosion occurred. In the end, the storehouse and perhaps some of the other buildings burned down. Archaeology proves that the storehouse burned but cannot determine when or by whom. In the other case “the Indians, it was said, were requested to draw a small mounted cannon by drag ropes. They laid hold, and when in an attitude most exposed, it was discharged, giving them all a frightful shock, and actually killing and wounding some of them.” (Williamson,200-201) If true, and Williamson is the first to admit these stories might not be, this was definitely not a high point in Native American/ English relations.

"A wonderful discouragement" – Sir Ferdinando Gorges

Conditions did not improve until spring with the arrival of two ships with supplies sometime in May. It is amazing the slowness at which news traveled back then; these supply ships brought the first report to the colony of the death of their benefactor Sir John Popham a year back on June 10, 1607, just ten days after the colonists sailed from England. The ships according to Strachey were “laden full of vitualls, armes, instruments and tooles, etc.” (Thayer,85) Within the month the ships were off again to England carrying the first report there of George Popham’s death.

The colonists rallied somewhat during the summer. Then Captain Robert Davies and the Mary and John arrived in September with news of a third death. Raleigh Gilbert's brother Sir John Gilbert had also died leaving the colony's leader as his heir. That was the straw that broke the little colony. Gilbert immediately planned to return to England to claim his inheritance thus leaving the little colony virtually leaderless. The colonists determined to abandon all their efforts. They dismantled as much of the property as possible, loaded anything of value onto Davies’ ship and theVirginiaand sailed back to England sometime in September or October.

Despite hardship and bad luck, the colony seems to have failed due to lack of leadership more than anything else. According to Strachey, Davies “found all things in good forwardness, and many kinds of furrs obteyned from the Indians by way of trade; good store of sarsaparilla gathered, and the new pynnace all finished”. (Thayer,85) No mention is made of the condition of the storehouse. It is unlikely things were very well off, and financially the little colony would need years before it could pay for itself even with good leadership and motivated colonists.

Of the colony's abandonment, Sir Ferdinando Gorges wrote that it was a "wonderful discouragement" that ended all formal attempts by the Plymouth Company to colonize New England until the Pilgrims arrived in 1620. The Plymouth Company became all but dormant with only Gorges and Judge Popham’s son Francis pursuing trade and fishing in New England. Although the abandonment was a set back to the settlement of Maine, Popham Colony did establish title for the English claims to Maine and New England, and theVirginiamarks the advent of Maine's shipbuilding industry.

And what became of theVirginia? We don't really know, but here are two possibilities. In 1609, the third supply fleet left Plymouth, England bound for Jamestown with 500 or 600 new settlers on nine ships. The 300 ton flag ship, theSea Venture, towed behind it a small pinnace that some historians feel may have been Popham Colony'sVirginia. About eight days from their destination a tremendous storm devastated the fleet. TheVirginiawas cut loose and never seen again. You mght prefer Robert Tristam Coffin's version; he said that theVirginia"finished its days, with good Englishmen chained in it, among the Barbary Pirates." Perhaps William Chandler provides the most thoroughly researched version in His book Ancient Sagadahoc. He says that the Virginia was indeed part of the 1609 fleet, but was not the pinnace in tow of the Sea Venture. Instead, and there is some documentation either way, the Virginiareturned to England for reasons unknown after a short time at sea and thus missed the hurricane or she was blown very far off course. The Virginia finally arrived at Jamestown two months after the other surviving ships in the fleet. Chandler postulates that the Virginia traveled back and forth between Jamestown and England for twenty years carrying tobacco and other products in one direction and young women and boys, kidknapped off the London streets, in the other. She may eventually have been wrecked off the Irish coast but this is unsubstantiated. Today, you can visit the Bath (ME) waterfront and the people at Maine's First Ship (http://www.mfship.org) to get a look at traditional ship design and building techniques as they build a replica of the Virginia to be used for educational purposes.

Two views of Popham today: The Virginia commemorative rock with Fort Popham in the background (left) and a view from the parking lot across the excavation site. David Higgins photos

“In Popham, we've got a slice of time." – Jeffrey Brain

Outside of Maine, Popham Colony quite literally disappeared from history except for the occasional mention. The accounts and Hunt’s map disappeared. Without documentation, Popham was hardly even considered to have been an actual and true attempt at colonization but rather just a plan that was not actually implemented.

Then in the 19th century, some major discoveries or rediscoveries were made. In 1849 The Hakluyt Society of London following in the footsteps of their namesake published William Strachey’s The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Brittania including the account of Popham Colony. Although written in 1619 it had never been published before and remained in manuscript form. Eight years later a copy of George Popham’s letter to James I was discovered by George Bancroft in the State Paper Office, London, and was donated by him to the Maine Historical Society. A number of small accounts and stories followed; several were French. It was enough for Maine historians to celebrate in 1862 with an extravagant day of speeches and a clambake at Fort Popham then under construction.

In 1875 Rev. Benjamn F. DeCosta of New York made the remarkable discovery of Davies account at Lambeth Palace, the official homeand extensive libraryof the Archbishop of Canterbury. The manuscript had already been rediscovered at least once before as is evidenced by the cover added to the original which reads: “The Relation of a Voyage Unto New England Began from the Lizard Ye First of June, 1607 by Captn Popham in ye Ship Ye Gift (and) Captn Gilbert in Ye Mary and John written by . . . . . .. & Found Among Ye Papers of Ye Truly Worspful Sr. Ferdinando Gorges Knt by ME William Griffith” (Thayer,35) That the manuscript made its way from Davies to Gorges is to be expected, but from there to Lambreth at an unknown time by the also unknown William Griffith to be found by a visiting American who was just searching for something historically interesting is priceless. The so-called Lambreth MS. was published in 1880.

One final lost piece of evidence surfaced around 1888 in Simmancas, Spain and became known at that time as the Simancas Map. It is the Plan of St Georges Fort by John Hunt. After making its way across the Atlantic in 1607 to England, Hunt’s plan, or a copy of it, made its way into the hands of Spanish Ambassador Pedro de Zuniga and from him to Philip III of Spain. Zuniga was a well-known spymaster and kept up a steady communication of events and information, often clandestine, with the Spanish government. England’s attempts at colonization were a frequent topic at this time period. For nearly three hundred years the Simancas Map, the only copy extant, was safe and sound in the Simanca archives and thus saved for historians to examine.

Over the last century many letters and other small documents have surfaced that assure us all that Popham was a legitimate colonial attempt that actually existed at the mouth of the Kennebec on the coast of Maine for a short year from 1607 to 1608. The last piece of the informational pie was to discover the exact location of Fort St. George and prize out what mysteries could be found there. Examination of the Hunt map and the general locale led away from the Civil War era Fort Popham site across the bay to Sabino Point.

The first real archaeological excavations were done in the 1960’s by Wendell Hadlock of the Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, Maine and were generally unsuccessful. Between 1994 and 2005 Professor Jeffrey Brain of the Peabody Essex Museum conducted a series archaeological digs based on locations determined by overlaying the Hunt map over a map of the point. As a result, he was able to uncover the storehouse, Gilbert’s house and another building. As he describes his work, "You're standing there uncovering a moment that hasn't been seen in 400 years. This is something they couldn't do in Jamestown, because it continued to be inhabited, 1607 is obliterated. But in Popham, we've got a slice of time." And so Popham may yet achieve some recognition and no longer be just a footnote to Jamestown and the Pilgrims.

Sources:Barry, Ellen. "Colony Lost And Found: Turns Out The Pilgrims Were Tardy" October 27, 1997.

http://www.weeklywire.com/ww/10-27-97/boston_feature_4.html. • Baxter, James Phinney, and Ferdinando Gorges. Sir Ferdinando Gorges and His Province of Maine. Including the Brief Relation, the Brief Narration, His Defence, the Charter Granted to Him, His Will, and His Letters. New York: B. Franklin, 1967. • Brain, Jeffrey P. Fort St. George on the Kennebec. S.l: s.n.], 2007. • Chandler, E. J. Ancient Sagadahoc: A Narrative History. Thomaston, Me: [Dan River Press], 1997. • Coffin, Robert Tristam. Kennebec: Cradle of Americans. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1937.• Hatch, Louis. Maine: a history. Somersworth, NH: New Hampshire Publishing Co., 1974. • Judd, Richard W. et.al. Maine: the Pine Tree State from Prehistory to the Present. Orono: UM Press, 1995.• "Relation of a Voyage to Sagadahoc" in Burrage, Henry S. (editor). Early English and French Voyages, Chiefly from Hakluyt, 1534-1608. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1906); online facsimile edition at www.americanjourneys.org/aj-032/. Accessed February 14, 2014. •Strachey, William, and Richard Henry Major. The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia: Expressing the Cosmographie and Comodities of the Country, Togither with the Manners and Customes of the People. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1849.•Thayer, Henry Otis. The Sagadahoc Colony, Comprising the Relation of a Voyage into New England; (Lambeth Ms.). New York: Research Reprints, 1970.

c2000, 2014 Pat Higgins