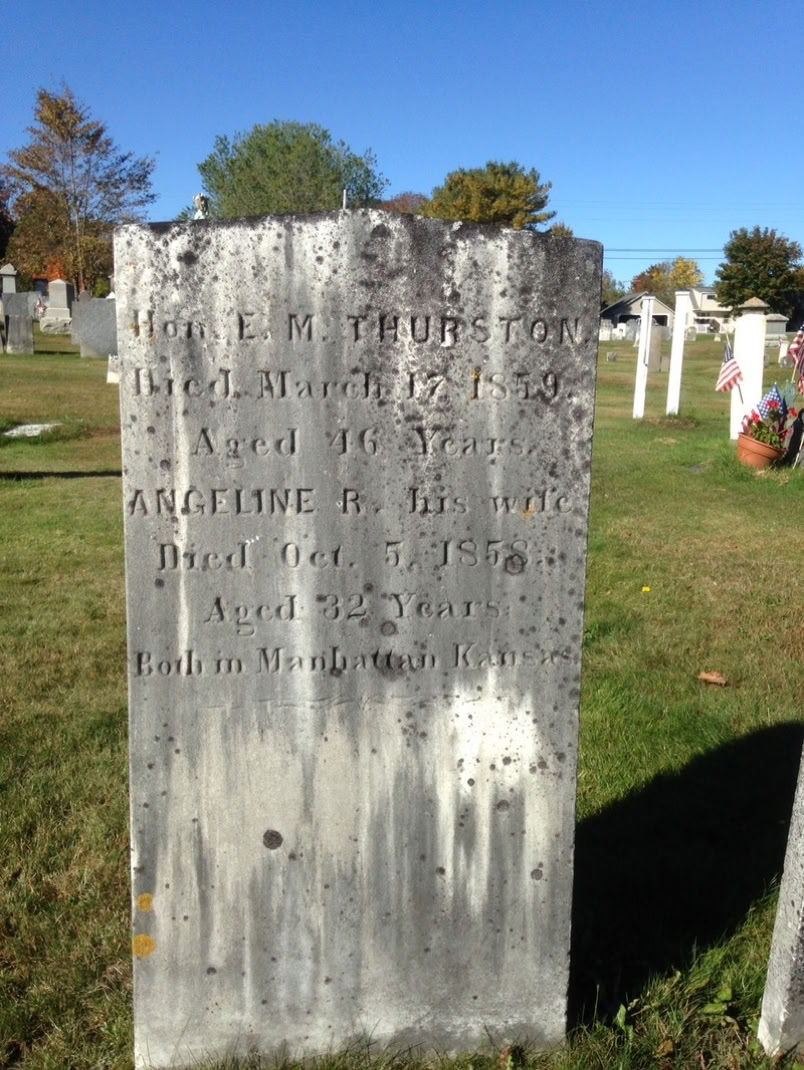

Both In Manhattan, Kansas

By Pat Higgins

A few years back, I stumbled across this stone in the Thomaston Town Cemetery. It's another one of those stones that records the loss of loved ones who are not actually buried there. Unusual in this seafaring town, this stone does not have anything to do with the loss of life at sea unless one wants to consider the allusion of the Great Plains as a sea of grass and wagons as prairie schooners.

E.M. (Elisha Madison) Thurston and his wife Angeline drew my interest because they died in Manhattan, Kansas in the period before the Civil War when the American people struggled mightily with the issues of slavery and the balance of power between the North and South. Kansas was at the epicenter of one of these struggles. Orator and Senator Stephen A. Douglas's Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 called for popular sovereignty in deciding whether the two territories would be admitted as slave states or free. In other words, the people in the territory would vote and decide for themselves what their state would be.

Realizing the importance of packing the vote, many abolitionists flocked to settle these territories. In 1854 the New England Emigrant Aid Company (originally the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Society) began sending what would total up to as many as 2000 "free soilers" who settled the towns of Lawrence and Manhattan, Kansas and beefed up the populations of Topeka and Osawatomie. They were, in turn, countered by angry pro slavers (dubbed border ruffians) largely from nearby Missouri. Violence was inevitable. You can read elsewhere about John Brown, Potawatomi, the Sacking of Lawrence, bushwackers and the War for Bleeding Kansas. Thurston’s role was in the building up of Manhattan and not the destruction and violence. But, as his obituary in the Colby Alumni Obituary Record states, he “shared in the “troubles” of that region and period”.

Born in Vermont in 1810 and educated in Massachusetts, Elisha M. Thurston graduated from Colby in 1838 where he studied for the ministry and gave the salutatory speech. He married Angeline R. Montgomery (b. 1826) of Cushing in 1843. An able educator, Thurston served as the principal of the new Charleston Academy and was elected to two terms each in the Maine State Legislature (1843 and 1844) and the Senate (1846 and 1847) representing Charleston. As Senator, he chaired the Education Committee, wrote the bill which would establish the state's Board of Education and promoted its county organizations and the instructional institutes which would advance teacher education. It was highly effective in a time when few teachers in predominantly rural Maine had themselves advanced beyond the 8th grade and many were under the age of 18 years. It was an important movement that not only trained teachers but also went a long ways toward equalizing education across the state and providing direction and guidance to town education committees and schools. Thurston was a frequent speaker at institute meetings and served ably as secretary of the Board from 1850-1853 at an annual salary of $1000 per year. By way of statistical impact, 1,686 teachers attended 13 institutes in 1847 alone; most had no previous education in the pedagogy of their profession. Unfortunately, the act was repealed in 1852, apparently the victim of party politics. As a noted educator and scholar as well as an able politician and manager, surely, the demise of the Board struck Thurston hard and may have prompted his move out of Maine to Kansas. With his background as a crusader for education it is not hard to understand Thurston’s interest in abolitionism and the Free Soil movement. There were, however, other reasons for his move as we shall see.

Leaving his family behind in Maine, Thurston set out for Kansas on October 6,1854. He traveled west in the New England Emigrant Aid Company’s fourth group leaving Boston October 17, 1854. It should be noted here that the Society did not sponsor or provide any funds to settlers. Instead they acted more as a travel agent by arranging transportation and temporary housing and helping out with settlement and land claims all for a fee. They were, in fact, an investment company bent on making profits for their shareholders, albeit for a worthy cause, and often invested in lucrative projects in the developing towns. Put away also any ideas of settlers traveling across the eastern US in wagon trains; these people traveled largely by train and switched to steamboats for the final leg up the Mississippi, the Missouri and then the Kansas rivers to Lawrence, Kansas where they stayed in a tent city before setting out to select their claims and plat (or map, organize and charter) their towns. It was a quick trip; Thurston was already exploring his new hometown by the end of the month.

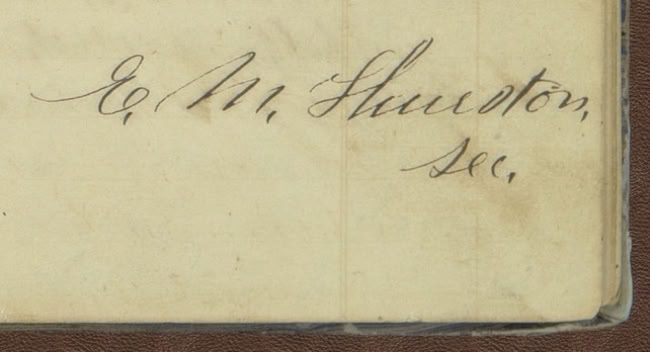

Research connects Thurston most frequently in records on the founding of Manhattan in Riley County, Kansas. The town developed from three tiny villages on the banks of the Big Blue River near its juncture with the Kansas River in what would become Riley County in northern central Kansas. It was conveniently located with ferry and river landing access to the Fort Riley-Fort Leavenworth military road and was an excellent investment. Thurston was part of a group of five (including two judges and a doctor) who claimed land for a town they called Canton in the fall of 1854 and wintered in little cabin at foot of Bluemont Hill. The following spring the Canton investors combined with nearby Poleska and Juniata together with a newly arrived committee of the New England Company, a settlement and investment company from Boston, to form a single town called Boston. (The new arrivals included Isaac T. Goodnow, a Rhode Island educator, abolitionist and an active Free-Soiler, who became a politician and developer of Kansas institutions Including the Manhattan college which would become Kansas State University. Of more importance to our story he kept a daily diary of brief entries on life in Manhattan in the 1850’s.) Thurston, his four partners and Goodnow became some of the twenty-four founding members of this new joint venture with Thurston serving as the recording secretary for meetings throughout 1855 when the town was being organized. The handwritten book of his minutes is in the possession of the Kansas State University Libraries and can be viewed online at the URL given below. His name shows up in the minutes and in occasional lists of expenditures for fees of $5 or so, and his signature graces the end of each meeting entry. In June 1855, with the influx of yet another round of settlers who arrived by steamboat, the town was again reorganized, and its name was changed to Manhattan.

The City of Manhattan was incorporated May 14, 1857, and the first election was held May 30. In 1858 the first school was built and the first religious services were held. The following year the first jail was built on the courthouse lot and at the other end of the spectrum Goodnow and others arranged for the incorporation of Bluemont Central College and began arranging it's financing. Throughout this period Thurston worked not only for the town and investment company but also as a surveyor and a lawyer. He had many business interests but also needed to attend to daily necessities especially in the earlier town period when goods and services were not as available. In a diary entry on 11/6/1855 Goodnow records that “Messrs Perry & Thurston picked corn half a day across the creek, & the other half on the Peninsula”. A few days later on November 10, he writes, “Call from Gen Pomroy & Mr Woodworth, & Mr Thurston They are on steam mill business.” In amongst the grander planning and building, as Goodnow testifies, crops still needed to be tended and harvested, wood chopped and lowly chicken houses built.

Meanwhile across Kansas and the nation things were not as constructive and up-lifting. The first election was held to choose a representative to the US Congress in November of 1854; Thurston had been in Kansas less than 6 weeks. A proslaver was elected and immediately contested; an estimated 1,729 out of 2,833 votes were fraudulent and cast by large numbers of slavery supporters pouring in from Missouri. A similar problem developed with the election for territorial representatives the following March at the time Manhattan then known as Boston was beginning to organize. Two Riley County men were the only Free Soil representatives elected in this election. Things went down hill from there. Congress sent a three man delegation from Washington to investigate. They decided that the election was illegal due to voter fraud and the representative body had no right to conduct government business. Despite their findings President Franklin Pierce, a New Hampshire native but nonetheless a proslave supporter, declared the proslave government to be in control and the Free Soilers to be insurrectionists. He had US Army troops sent to Topeka to order the dispersal of the opposing Free Soil legislature in 1856.

Life was not to remain golden out on the Kansas frontier for the Thurston's either. In the fall of 1857, after three years away, Thurston returned to Maine where he divested himself of all property there, packed up his family and returned to Manhattan for good. On October 5,1858, hardly a year after her arrival in Manhattan, Angeline Thurston died suddenly from typhoid and was buried there in the Sunset Cemetery. In addition to her husband, Angeline left behind four young daughters. Death in childbirth was common as was that caused by any number of diseases also prevalent at the time such as cholera, typhoid, pneumonia, consumption or even measles. Goodnow refers constantly in his diaries to chills and fevers suffered by his friends, family and even himself, so disease was an issue and often fatal in the days before antibiotics.

The work of organizing the town began in earnest. Starting with a log blacksmith shop, a dugout and a tent fortified by sod walls, the group built several crude houses. Territorial law allowed 320 acres of land to be purchased for the establishment of a town; two additional tracts of land were purchased that spring. A constitution was written and adopted. Stock was distributed to the original founders and assigned to educational, religious and commercial purposes plus more shares were set aside for discretionary purposes that might arise in the future. The immediate town area was surveyed and included market squares, a 45 acre park, river landing, ferry, warehouse and business sites. Incentives were offered to encourage businesses. The arrival of the steamboat crowd put more people to work. By the first of the following year, the new settlers added another 15 houses, 10 were prefabricated and carried aboard the steamship. At first land speculation and trade drove the development of the town but soon small scale manufacturing began. The New England Emigrant Aid Co. invested in a steam powered gristmlil and and a sawmill. Hotels, retail stores, restaurants and offices offering professional services opened. Goods arrived from the East at the ferry landing and, soon enough, agricultural products were shipped east.

Another source of information on the development of Kansas is in newspaper articles and editorial letters of journalists who traveled about the area. Julia Louisa Lovejoy was an early settler in Manhattan who soon moved on to become a noted writer and newspaper correspondent. Her son was the first child born in Manhattan, and the family had many friends there. A few years later on a trip back to Kansas she published a series letters in eastern religious newspapers describing what she saw in Kansas then and what she remembered of her previous life there. Her May 1858 ‘letter' describing changes brought about in Manhattan in just a few short years including “the tastefully built residence of Hon. Mr. [E. M.] Thurston, of Maine, one of the original proprietors of the town. I did not learn the number of houses in town, but noticed some beautiful private residences, large hotels, a number of costly stone buildings, for various purposes, and a large two-story stone building, for school purposes. The Methodists have a stone church they hope soon to have completed, and the Episcopalians and Congregationalists intend to build immediately, we were told.” Manhattan was on its way to becoming a bustling commercial town largely based on the importance of its location as was recognized by the founders; it was at the junction of important river routes and military roads that soon were used by many travelers on their way west to Pike’s Peak and the Colorado gold fields. All this in just a couple short years.

In the period 1854 to 1861 when the Civil War began in earnest, Kansas had ten different governors, numerous capitals (one lasted only 6 days), and in 1857-58 had both a free and a slave government operating at the same time. Four constitutions were written: Topeka,(free)1855 ; Lecompton, (slave) 1857; Leavenworth, (free) 1858; and Wyandotte, (free) 1859; Our man E.M. Thurston was one of the three Riley County men sent to the Leavenworth Convention. The Free-Soil constitutions all went beyond the slavery issue in that they all included some form of suffrage for Blacks, Indians and women. Despite the fact that Free Soilers were winning control of Kansas and an election had overwhelmingly dismissed the proslave constitution, President James Buchanan took the Lecompton Constitution to Congress in 1858 with the recommendation that Kansas be admitted as a slave state. Partisan fighting in Washington and Kansas took up the better part of three years. It was a moot point; with Lincoln’s election opposition to statehood died as southern states withdrew from the Union. Kansas joined the Union January 29, 1861 as one of the last official acts of the Buchanan era. And so, although Manhattan managed to avoid the outright violence that occurred in this period, it existed in the midst of unavoidable and highly contentious political turmoil.

Make no mistake that violence was not on the table as far as both sides were concerned at the start of the War for Bleeding Kansas. Between 1854 and 1858, nearly one thousand of the new breach loading Sharps rifles were shipped from the East by abolitionist supporters to Free Soilers in Kansas. They were shipped in secret in boxes marked ‘Beecher’s Bibles', named after Rev. Henry Ward Beecher who thought that the rifle would likely be more listened toby proslaversthan the Bible. In 1856 proslave Missourians began to escalate their activities and virtually cut off Kansas emigration via customary river routes and turned back many parties. Emigrants from the East soon turned to land routes. On May 21, 1856 Border ruffians sacked the Free Soil stronghold of Lawrence burning the hotel and destroying two newspapers. Legendary madman John Brown who arrived in Kansas in 1855 to quite literally fight against slavery led a retaliatory attack on Pottawatomie four days later in which five proslavers were brutally hacked to death with swords. Later that summer, armies of proslavers crossed the border and both sides engaged in attacks, looting and burning of crops and homesteads. A band of 400 proslavers attacked Brown at Osawatomie and totally destroyed the town. (Brown eventually moved on to a higher calling and met his fate in 1859 at the Harper’s Ferry federal armory in Virginia.) Finally, the acting governor at the moment prevailed on both sides to accept a fragile peace, but the following years were not without moments of bloody disagreement. The violence that Manhattan escaped was a hate-filled precursor to the war that was only a few years off.

The Colby Obituary Recorddescribes Thurston as less than robust and prone to a (unnamed) debilitating illness: “1844, Aug. Health failing, he was confined to his bed for nearly a year.” And “After 1852, he was for sometime laid aside from business by sickness.” In her May 22, 1855 letter home from Kansas, Julia Lovejoy describes remarkable health benefits from the clean air using Thurston as her example:

“A gentleman from Maine, a graduate of Waterville, and for years past teacher in the Charlestown Academy, who was, to all appearance in the last stages of consumption, given over by his physicians to die, as a last resort came to Kanzas, has lived here through the winter, and now is so well he labors constantly, and at night wraps a buffalo robe about him, and throws himself on the open prairie, with no covering but the canopy of heaven.”

A little more light is shed on Thurston’s health by Clarina I. H. Nichols, a writer, teacher and early feminist as well as an outspoken leader in the temperance and abolitionist movements. She traveled to Kansas in the same Emigrant Aid group as Thurston and gives us a more specific health report on Thurston himself. She wrote and published a number of letters to eastern newspapers about the abolitionists of Kansas and wrote on April 7,1855 of Manhattan,:

“Several of my old friends have removed there, and others of our party last fall are going there. E. M. Thurston, Secretary of the Board of Education in Maine for several years, who came out in our party last fall as a last hope against supposed confirmed consumption, is there. He has regained his health and recently footed it from Kansas [City] to Wabonsee, 120 miles. The emigrants have been generally healthy; few deaths or severe cases of illness in proportion to their numbers.”

Perhaps abolitionism was not the only reason for Thurston’s move out of the damp Northeast. Unfortunately, Lovejoy and Nichol’s glowing reports of the healthy living properties of Kansas were not to rescue Thurston from consumption in the long run. According to Goodnow’s sparsely written diary: "3/17/1859 E.M. Thurston died - consumption and was buried 3/19.” The Colby alumni book describes his death as a “violent hemorrhage of the lungs”. He rests next to his wife in the Sunset Cemetery surviving her by six short months. His death came not quite five years into the development of his new city and cut short his term as mayor.

A note on consumption: Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries consumption, now called tuberculosis, was the leading cause of death in the US. For the preceding 200 years it had raged across Europe and the US and was known as the Great White Plague. It is estimated to have killed a billion people worldwide in this period. Before the discovery of the bacteria that caused consumption in 1865, it was not understood to be contagious. In fact the mid 19th century marked the beginning of our understanding of germs in general and the part they play in spreading disease. Consumption was, instead, considered at the time a disease of the urban poor or even quite possibly hereditary. Victims would waste away and suffered from fevers and night sweats. They often coughed up phlegm and blood. Before 20th century vaccines and antibiotics there was no cure. Rest, good food and outdoor exercise were considered the best treatment in this period. Few recovered and relapse was common, thus Thurston’s long bouts of confinement and perhaps a part of his reason for going west. Death by consumption was often long, slow and by no means romantic as depicted by the art and literature of the times.

E. M. Thurston’s time in Manhattan was short especially compared to others like Isaac Goodnow who was a viable leader up until his death in 1894 at age 81. Manhattan did name a street after him - Thurston Avenue, but his tasteful house is apparently no longer standing. All in all, Thurston would likely be satisfied with the growth of Manhattan and especially in the establishment there of one of the state’s first three colleges which opened its doors in 1860 as Blue Mont Central College and was soon turned into the state’s land-grant college and later Kansas State University.

The Thurston’s had five daughters, all born in Charleston. Annie Montgomery, born in 1854, died in infancy in Charleston, and Ella Adelaide, born in 1852, died in childhood in 1860 in Topeka, KS. The remaining three survived into adulthood: Emma Leoline (1847-1890), Margaret Ann (1849), Nettie Florence (1856). After their parents deaths, the girls were taken in by Episcopalian minister Rev. J.O. Preston and his family. They attended a seminary for young ladies in Topeka and the new college in Manhattan, training as teachers. A testimony to their father’s career in education, the girls each taught in Kansas public schools for some years before moving to California. None of the three are mentioned in the family genealogy as marrying and having children of their own.

Someone back home in Thomaston, Maine, ostensibly a member of Angeline’s family, erected an oddly plain stone as a commemoration in the Town Cemetery. Names and dates are crammed in the top half of the stone, and there is no ornamentation or sentiment but just this: “both in Manhattan, Kansas”. There’s a story in that.

Partial List of Sources:

Elisha Madison Thurston." Alumni of Colby University Obituary Record from 1873 to 1877. including Notices of All Alumni Whose Decease Has Been Learned from July, 1873 to July, 1877. Supplement No. 2. Waterville: Printed for the Alumni, 1870. 32. Web. 17 Mar. 2017. <https://books.google.com/books?id=xU9AAAAAYAAJ&dq=E.M.+Thurston+%2B+Colby&source=gbs_navlinks_s>.

“Elisha M. Thurston.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=91379046 5 June 2012. Web 20 March 2017.

Hambone, Joseph G. "The Forgotten Feminist of Kansas, 1: The Papers of Clarina I. H. Nichols, 1854-1885." Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains. Kansas Historical Society. Spring 1973. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <https://www.kshs.org/p/the-forgotten-feminist-of-kansas-1/13232>.

Isaac T. Goodnow. "Isaac Goodnow's Diaries | Riley County Official Website." Isaac Goodnow's Diaries | Riley County Official Website. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <http://www.rileycountyks.gov/1077/Diaries-of-Isaac-T-Goodnow>.

Koehler, Christopher. "Consumption, the Great Killer." Modern Drug Discovery. American Chemical Society, Feb. 2002. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <http://pubs.acs.org/subscribe/archive/mdd/v05/i02/html/02timeline.html>.

Lovejoy, Julia Louisa. "Letters From Kanzas." Kansas Historical Quarterly. Kansas Historical Society, 1942. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <http://www.kshs.org/p/letters-from-kanzas/12893>.

Maine. Department of Education. "150 Years of Education: Part I - Education in Maine Prior to 1900.” Maine.gov. April 1970. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <http://maine.gov/education/150yrs/150part1.htm>.

Maine. Department of Education. ”Education in Maine." Google Books. 18 Nov. 2002. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <https://books.google.com/books?id=OpmgAAAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA75&dq=Education%2Bin%2BMaine%3A%2BReport.%2B1880%2B%22E.M.Thurston%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi-opmLx-bSAhWp7YMKHWshB4cQ6AEIIDAB#v=onepage&q&f=false>.

Records and constitution of the Boston Association, Apr. 3 1855 to June 29th 1855, and also of the Manhattan Town Association, July 7th 1855 to Jan. 7th 1856. Book one by Boston Association (Manhattan, Kan.); Thurston, E. M.; Manhattan Town Association (Kan.) 1855. Web. 20 March 2017. https://archive.org/details/KSULBostAssoc1855F676R43

"Territorial Kansas Online." Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <http://www.territorialkansasonline.org/~imlskto/cgi-bin/index.php?SCREEN=topics>.

Note: This URL will get you into the KSHS/UK system; it is well indexed and easily searchable. I used and read many, many pages found here.

Thurston, Brown. Thurston Genealogies. B. Thurston, 1892. Web. 20 March 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=SBBWAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Thurston+Genealogies++ebook&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjI7_i4jMrRAhUI_IMKHe5VDsYQ6AEIMjAA#v=snippet&q=6226&f=false

US Department of the Interior. National ParkService. National Register of Historic Places."Late Nineteenth Century Vernacular Stone Houses in Manhattan, Kansas Riley County Kansas." City of Manhattan, Kansas. Web. 20 Mar. 2017. <http://www.cityofmhk.com/DocumentCenter/Home/View/4680+>.

C2022 Pat ?Higgins